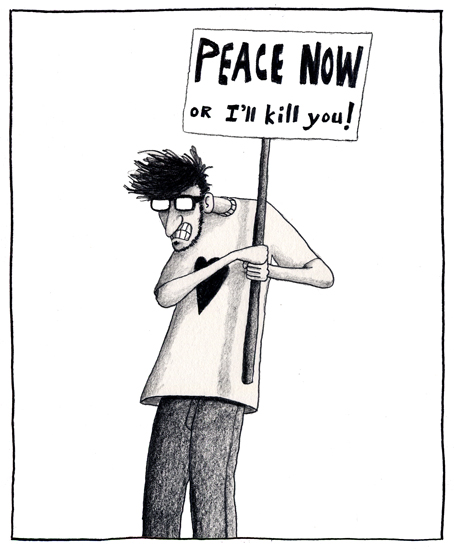

Editorial cartooning has never had a Mozart, much less a Bob Dylan, although there have always been a shitload of Donovans in the profession. Always. While the best cartoonists might be able to, on occasion, press themselves up against the high ceiling of creative expression, none have been able to go beyond that ceiling into the diseased and limitless sky where real artistic relevance resides, indefinable and eerily divine, porcupined with existential boners of both elite and lowbrow curiosities and pocked heavily with heartbreaking vulnerabilities, all the while absolutely oozing with a charitable self-absorption that is as tenuous and indestructible as light itself. By ignoring the stylistic boundaries that are self-imposed by the cartoonist’s commitment to branding and avoiding any literal association with any specific political or social agenda, a piece of art will prostrate itself to an infinite number of interpretations and, therefore, an infinite number of uses by an infinite number of people. Conversely, an editorial cartoonist is only successful if he can get the number of viable interpretations of his work down below two, and he is only expected to express opinions about other people’s problems, never his own, which is more in line with the responsibilities of a mother-in-law or Jiminy Cricket than with an artist hoping to starve to death on his own integrity.

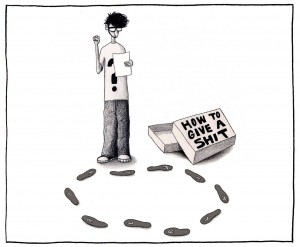

Editorial cartoonists, thusly, do not practice art as much as they practice journalism, and as journalists they are, at least the most successful ones are, nothing more than polite hecklers of despicable men whose faults are glaring enough to serve journalism’s shorthand; that is, whose faults are so obvious that they provide a point of fact that allows the raison d’etre of the cartoon to make sense to as many people as possible. (Example: What makes George W. Bush the most lampooned U.S. President worldwide in history, surpassing all 20th Century Presidents combined, is the fact that you don’t need a house of mirrors to confirm that he is a complete asshole from every angle.) In that way, an editorial cartoonist sheds no new light on a subject, but rather relies on the manipulation of pre-existing prejudices to gently cajole his fans into continuing to agree with themselves. He is a jingle writer for the op-ed page with his commentary usually fitting as comfortably into the whimsy of his readers as the Oscar Myer Weiner song. Paid by advertisers who provide his publication’s income, it is his job to package and sell cultural criticism in a way that is fun! and completely innutritious, helping the country to remain so deliciously democracy-flavored while the First Amendment remains untouched like a musket over the hearth of our national identity, too precious to ever fire, all the marksmen of such a weapon long dead, their limbs and vocal cords murdered into coins and statues and lore.

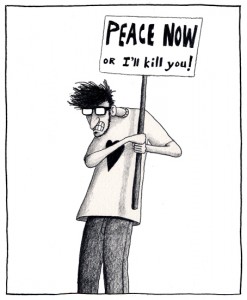

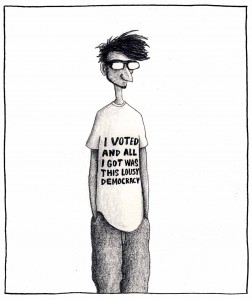

And when I compare myself with all the cartoonists whose work I so frequently and tempestuously abhor, I realize that what I do, while perhaps stylistically more adventurous than others, is not substantively different than the profession’s most common toilers. I guess that the outstanding difference between me and other cartoonists, at least the ones that I’ve spoken with or whose personal stories I’ve read about, is that they all respected the field of editorial cartooning enough to want to be a part of it, citing Herblock and Bill Mauldin and Paul Conrad as their biggest influences, while none of my primary influences for what I do were ever cartoonists; they were Woody Allen, Noam Chomsky, John Lennon, Jack Benny, Bugs Bunny, Voltaire, Benjamin Braddock and all the dogs my family had while I was growing up. In fact, cartooning for me is the equivalent of waitressing until my true gifts are able to earn me some serious dough. My gifts? Well, right now, I have two that are running pretty much neck and neck: writing unpublishable treatises on what’s wrong with everything and everybody and rewriting unpublishable treatises on what’s wrong with everything and everybody. I, like every other writer and musician and painter who I’ve ever hung out with, am a hamster in a wheel motivated by the smell of his own ass. Like excessive masturbation, some part of me believes that the repetitive nature of writing and rewriting will eventually magnetize my intellect and make it so that other intellects will be inexorably drawn to what I do. I’m hoping that one day my brain will be charged sufficiently to fuck up clocks when I walk down the street and to pull the pacemakers out of the chests of ailing poets and to yank the chains from the necks of dogs straining to run, crap anywhere and hump like, well, dogs.

I suppose that an argument could be made that the repetitiveness of my writing and rewriting is no more admirable than the same repetitiveness that allows a sizable portion of all editorial cartoonists to stay in business, completely independent of how good or bad their work may be, that repetitiveness being daily syndication. Seen everyday, many cartoonists inevitably become like family members to some readers and, like real family members, it may take them decades to say or do anything worth repeating to somebody unrelated. Garry Trudeau, for example, while he might’ve earned the moniker of great innovator for bringing politics to the comic strip format, hasn’t had anything to say for thirty years, yet I’m sure that if I saw the car he drives I’d think that he was still culturally viable. He’s not, and he’s in 1400 newspapers. His notoriety simply comes from being a brand name that people recognize, no more imperative to the national debate on politics than a Rubik’s Cube.

Then, often times, along with the repetitiveness of the cartoonist’s artwork, comes, through daily bombardment, the bogus reinforcement of the cartoonist’s occupational reputation as a dangerous character, the type of outlaw who tears truth a new asshole every time he sets pen to paper, his actual abilities of no importance whatsoever to the equation. Example? Two words: Ted Rall, purported to be the most dangerous progressive cartoonist working today, which he is, if the furthest you’re willing to lean to the left is George McGovern. I’d qualify Rall’s dangerousness this way: the flabbiness of his vaguely liberal commentary only contributes to the guarantee that the general public won’t recognize real radical humor when or if it ever again appears in the culture. It’s like conditioning people to define irreverence as being what prop comedian, and all around goofball, Gallagher does when he uses a sledgehammer to splatter his audience with the guts of a watermelon, so that if somebody like Lenny Bruce ever comes along and uses an analogy to splatter his audience with the metaphorical guts of some exploded societal myth better blown apart than allowed to propagate, nobody will know how to react, the definition of irreverence having been hijacked and outfitted with speed bumps and NO SPITTING signs. And, of course, a laugh track.

(And, speaking of being unfairly labeled with the reputation of dangerous cartoonist, I have to say that Paul Conrad’s infamous inclusion on Nixon’s enemies list loses some of its prestige when one looks at some of the other people on the list with him, particularly those closer to the top; people like Carol Channing, Bill Cosby and, news to me, the Che Guevara of the Hollywood sub-elite, Tony Randall. Suddenly, the list becomes what it really was: the work of a complete imbecile whose opinion of who was naughty and who was nice shouldn’t merit anything but embarrassment and pity. Being proud of appearing on such a list is not unlike being proud that your neighbor’s retarded uncle calls you a Mr. Poopy Pantsey! every morning when you step outside to pick up the paper.)

Now, lest anybody think that I dislike all other political cartoonists or that I think their work is substandard and not worth looking at, the opposite is true. Political cartoonists are important merely because they help to remind people that politics are not so complicated that every Tom, Dick and Harriet shouldn’t have an opinion about them. They should. Editorial cartoons help prevent the authoritarian powerbrokers of society from suffocating the democracy completely with the bogus idea that only professional politicians and high powered businessmen should be allowed to engage in the public debate about how government should function. I just want to point out that when it comes to an editorial cartoonist speaking truth to power and championing the causes of the downtrodden and the politically shatupon, Tom Tomorrow or Michael Ramirez or Jeff Danzinger or Mike Luckovitz or Tom Toles are by no means the best that there is. No editorial cartoonist is. In fact, they are all often times decades, even centuries, behind a very long line of writers and painters and sculptors and musicians whose insights and ruminations on life better exemplify what really deep and thoroughly engrossing commentary should look like at its most insightful and profound.

Specifically, when one considers the work of people like Mark Twain, Honoré Daumier, Frederick Douglas, Pablo Picasso, Oscar Wilde, Allen Ginsberg, Karl Marx, Louis Armstrong, Henry Miller, T.S. Eliot, Francisco Goya, William Shakespeare, Jack Kerouac, Aristotle, and on and on and on, the qualification of any editorial cartoonist as being anything even approaching a genius of creative expression or radical behavior becomes problematic at best, outrageous at least. Specifically, the occupation of cartoonist is too narrowly defined to be able to contain within it something so vast as the concept of genius, the same way that a tournament level nose picker will never compete in the Olympic Games, no matter how good he is.

Drawing on the definition that I started with, the one about editorial cartoonists being more like journalists than artists, it might be informative to think of them, all of them, as the print equivalent of broadcast journalists, with somebody like Paul Conrad being the equivalent of Walter Cronkite. His longevity is obvious, his work ethic is ridiculously Catholic, his likeability immense, but one should not be afraid to ask if Walter Cronkite is a journalist whose gifts justify his legend or does his notoriety come largely from the celebrity of his celebrity?

In other words, just because he has been the journalist who we most often recognize seated at the table closest to the action unfolding on our national stage, and just because his is the voice that we’ve been conditioned to hear as the most reliable when it comes to telling us what’s going on and why, there’s no reason I see to believe – particularly after reading the words of real newsmen like Bill Moyers and Robert Fisk and Bob Scheer and Tariq Ali and Seymour Hersch and Lewis Lapham and Chris Hedges – that the person seated closest to the action is the one with the clearest view. Typically, he’s the last one to know where the exits are and, sadly, also the last one the coroner is able to identify after the fire sweeps through, all of a sudden, from the back of the room where the riffraff and well-to-do typically congregate to smoke and bullshit and assimilate their humanity.